This week’s topic: Is Critical Theory, taught by Academic MFA programs useful in learning the craft of writing? Welcome to our ongoing series of creative writing discussions. We will regularly pick a subject related to

This week’s topic: Is Critical Theory, taught by Academic MFA programs useful in learning the craft of writing?

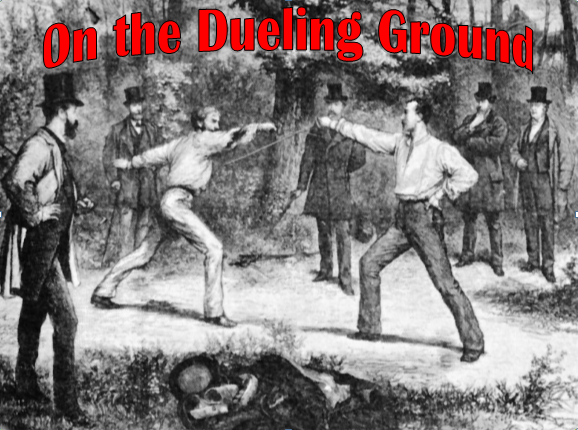

Welcome to our ongoing series of creative writing discussions. We will regularly pick a subject related to writing and have two of our writers engage in a friendly wordsmithing duel on the topic under aliases.

*Editorial Note: Debates are solely thought experiments and do not reflect the position of New Pulp Tales personnel.

Titanic Tim: I say that ‘Academic’ writing programs are hothouse flowers. They teach writing in a parochial style focused on a narrow range of topics and they’re only meant to please a very insular academic audience. Moreover, the modern academic environment, with an emphasis upon the mythic figure of the Auteur and art as an extension of personality, insulates against the kind of unfiltered criticism that writers need to hear in order to improve. Of course, that’s aside from the larger issue of “Critical Theory” (which is not actually theory) militating against the kind of traditional artistry and craftsmanship that makes for good writing. Is it any wonder that the novel stereotypically birthed from an academic MFA program might be read by eight people, if you include the author’s parents and their five cats? An apprenticeship in the commercial market, without the benefit of an MFA program, has the virtue of teaching a writer that they aren’t God’s gift to humanity and instilling the discipline needed to learn their craft. Cheers to every working stiff who has a stack of rejection notices pinned to their wall!

Raymond Coffee: I both agree and disagree with your statement about Critical Theory. History proves you correct in attaching militating ideology to it. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd edition states on page 1108 the term was devised by Max Horkheimer in 1930 at the University of Frankfurt after leaving home to escape the family textile business because “he could not accept the exploitation of labor upon which [the family business] was based”. Let’s be clear—I acknowledge Horkheimer and his colleagues were preaching the culture industry of the west was run by the overlords of western capitalism for their own benefit and is rooted in ideas of change. But since that time, much has changed, and the emphasis of influence has grown from its socialist roots to keep pace with current social issues and large ideas designed to pull back the curtain on dogmatic beliefs served up by news and social media as a form of reality.

Titanic Tim: Change. Not truth. Not fact. Foucault, Derrida, Lacan, de Man, etc. were at least clear on that point, when you could puzzle out their obscurantist blather. Critical Theory “[keeps] pace with current social issues” by assigning all manner of hidden motives and conspiracies to anything and everything. No whole text or utterance bears meaning, they’re all just parts assembled into instruments of power, built by competing power groups, that have to be disassembled to see how they “work,” according to the hermetic principles of Critical Theory. The Cult of the Critical has one credo, “There is no world but Utopia and We are its Prophets.” They have to delegitimize their competitors to obtain that power for themselves, so as to bring about their “change.”

Raymond Coffee: Moving on, I suggest studying the craft of writing through contradictory points of view, that clash of ideas that Critical Theory may bring, is healthy and if done well can help one’s own work to avoid some of the pitfalls that writers, especially young ones, tend to make because they are passionate beyond their knowledge of the issues they write about.

Titanic Tim: Agreed, but Socrates used his method to examine ideas and motives and Aristotle showed how to cut through sophistry over two thousand years ago. We don’t do chemistry with alchemy or treat mental disorders with phrenology, so one doesn’t need the aid of pseudo-theory wrapped in pseudo-scientific jargon to analyze a text. For that matter, Quentin Skinner and the Cambridge School of historians were discussing contexts and textual intent early as the 1960s, without a whiff of Marx. And more useful for actual writing is J.L. Austin’s speech-act theory, in How to Do Things with Words.

Raymond Coffee: But don’t you agree that studying one’s work closely can also help the mechanics of writing such as weaknesses in plot, character irregularities, story arcs that don’t make sense or need tweaking? I propose both literary and genre minded authors must learn the basics of writing to become masters at their craft.

Titanic Tim: True, but Critical Theory won’t take you one step in that direction. The text is always an excuse to discuss something else.

Raymond Coffee: Let’s talk about your statement that ‘Academic Programs’ “writing in a parochial style focused on a narrow range of topics…only meant to please a very insular academic audience.” Are you saying ‘Academic’ MFA programs are limiting students to specific philosophies, including the activism we see on campuses today? Whether or not a school turns students into activists, I believe, says more about the individual than the school. If the student is not getting the knowledge needed to write well, they are not in the right place for them, a problem they can correct.

Titanic Tim: An impressionable undergrad going for a BFA might be a living refutation of that axiom. A campus can be a retreat for contemplation, but it can also be an echo chamber where young minds, moving by small degrees, eventually find themselves maundering and mumbling the incantations of their professors with leaden tongues. The mobs at Mizzou and Evergreen State College are an inevitable result, when they haven’t awakened from their stupor.

Raymond Coffee: But, Titanic Tim, students in a good graduate program will experience plenty of deadlines, tough assignments and crucibles of pain to produce the work necessary to graduate. That hard work should burn the ‘wax from the mold’ as it were. If they are good programs, both ‘Academic’ programs whose roots are steeped in “–isms” such as Deconstruction and Poststructuralism, Feminist Theory and Criticism, Marxism and many more, and Genre Fiction programs with its countless choices of genres, sub-genres and cross-genre mash-ups, will use workshops to expose writers to criticism, a necessary component to become successful in one’s craft.

Titanic Tim: Again, one would hope. But the academy, in the throes of those “-isms,” can see art as just an artist creating their own meaning, a personal expression incommensurable with any other. Under those conditions, it can become rather hard to critique work in a workshop setting. Theory and craft have to be separated, if critiques are to function at all. Programs with a genre fiction emphasis are the most likely to put theory and craft on separate tracks. Theory gets taught and then put on a shelf while students get down to the business of writing actual stories. In that way, they are more like the school of hard knocks.

Raymond Coffee: ‘Academic’ MFA programs are not all bad. On that I think we can agree…I would hope that most MFA programs, whether literature focused or ‘genre’ focused, try to teach their students skills that move them from beginning scribes to seasoned authors with voice. The goal of all credible creative writing programs is to produce graduates with the skills to write a grammatically correct, smooth sounding, interesting document that others might like to read. It is up to potential students themselves to discover which institution and program will be the best fit for them.

Titanic Tim: So, I would hope as well. But as B.H. Myers makes clear in his teardown of the “literary establishment” in the Atlantic (as pertinent now as it was in 2001), “A Reader’s Manifesto,” the belief of that establishment is that “serious literature” is free to disregard such plebian concerns as grammatical sentences, so long as it can be sold as defying or subverting something, whatever the target is this week. The halcyon days of Literary Modernism are over, where Eliot, Woolfe, Hemmingway, Pound, et al. worked to produce new literary forms. Of course, they were also conversant with the tradition of Western literature, such that they knew what the hell they were doing. Today, experimentation is affectation. That some programs might walk the tightrope and escape this hazard doesn’t remove the absurdity that such a hazard exists. Neither does it remove the disadvantage of being cloistered in the ivory tower, secluded from a general audience of more varied experiences and tastes.

Raymond Coffee: Titanic Tim, I can see you’re not a fan of Critical Theory. But that’s all the time we have this week. Check back soon for another dueling discussion related to creative writing.